|

The Power of Irony: Brahms' setting of Schiller's "Nänie" Before investigating Brahms' work, we wish to clarify our use of the term "irony" in discussions of music. A musical idea may be said to have "meaning" for many reasons; perhaps it suggests a certain harmonic treatment, or conveys an affective state such as melancholia or exuberance. However, musical ideas are by nature ambiguous, and susceptible to dramatic alterations of "meaning" by a change in the harmonic or rhythmic context, changes in tempo, or through a revealed contrapuntal relationship to another idea, or to itself via the technique of stretto. The process of "musical development," which is what distinguishes "classical" or "art" music from folk or popular music, is the process of the evolution of musical ideas in the course of a piece, so that their ambiguities are exploited to reveal new "meanings" in a dramatic way, utilizing the element of surprise. This is what we mean by musical irony: a tension or incongruity between real and expected results, in the service of a higher, overarching idea, which is the unifying conception behind the composition. John Keats, in his "Ode on a Grecian Urn," wrote that Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard. Are sweeter; this describes the "higher hypothesis" which is "heard" only in the mind, and gives a work of classical music its potency. "Musical irony" describes the process by which this hypothesis is revealed, via a progression of smaller revelations of unexpected "meanings" in ambiguous motific material. Nänie, or in English Nenia, was the Greek goddess of funerary lamentation. Her name has also come to mean a dirge of lamentation and praise of a deceased person, sung to a flute accompaniment by a hired mourner. Schiller's poem is yet another example of a poetic treatment of the paradox of mortality, or if you prefer, the paradox of immortality. The great composers were hesitant to set Schiller's works to music. As Beethoven put it, "Schiller's poems are very difficult to set to music. The composer must be able to lift himself far above the poet; who can do that in the case of Schiller?" Brahms thought long and hard before making the attempt.

Brahms' Opus 82 setting of Schiller's poem, for chorus with orchestra, provides a clear and powerful example of Brahms' approach to musical irony. The piece begins with an instrumental introduction, which features the oboe, enunciating a melody accompanied by winds and pizzicati strings. It begins in the key of D major, but feints right away toward a tonal center of G lydian before meandering back to the home key. In the context of the first hearing the melody seems sentimental, almost banal:

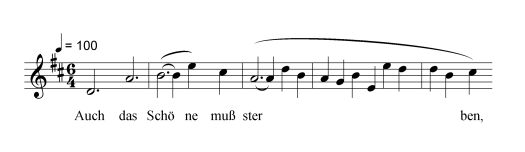

This is followed by the sopranos, who sing the first phrase of the poem, in a melody which seems disarmingly casual, considering the gravity of the text:

However, the truth is soon revealed: the sopranos are singing the subject of a four part fugue, and as the other voices enter, the contrapuntal potentialities of that subject emerge. By the time all four voices have entered to sing the first phrase of the text, it has been transformed into something much richer and more meaningful. Here for reference is a full translation:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Auch das Schöne muß sterben! Das Menschen und Götter bezwinget,

|

Also Beauty must perish! What gods and humanity conquers,

|

|

Nicht die eherne Brust rührt es des stygischen Zeus.

|

Moves not the armored breast of the Stygian Zeus.

|

|

Einmal nur erweichte die Liebe den Schattenbeherrscher,

|

Only once did love come to soften the Lord of the Shadows,

|

|

Und an der Schwelle noch, streng, rief er zurück sein Geschenk.

|

And at the threshold at last, sternly he took back his gift.

|

|

Nicht stillt Aphrodite dem schöne Knaben die Wunde,

|

Nor can Aphrodite assuage the wounds of the youngster,

|

|

Die in den zierlichen Leib grausam der Eber geritzt.

|

That in his delicate form the boar had savagely torn.

|

|

Nicht erretet den göttlichen Held die unsterbliche Mutter,

|

Nor can rescue the hero divine his undying mother,

|

|

Wann er, am skäischen Tor fallend, sein Schicksal erfüllt.

|

When, at the Scaean gate now falling, his fate he fulfills.

|

|

Aber sie steigt aus dem Meer mit allen Töchtern des Nereus,

|

But she ascends from the sea with all the daughters of Nereus,

|

|

Und die Klage hebt an um den verherrlichten Sohn.

|

And she raises a plaint here for her glorified son. |

|

Siehe, da weinen die Götter, es weinen die Göttinnin alle,

|

See now, the gods, they are weeping, the goddesses all weeping also,

|

|

Daß das Schöne vergeht, daß das Vollkommene stirbt.

|

That the beauteous must fade, that the most perfect one dies.

|

|

Auch ein Klaglied zu sein im Mund der Geliebten, ist herrlich,

|

But to be a lament on the lips of the loved one is glorious,

|

|

Denn das Gemeine geht klanglos zum Orkus hinab.

|

For the prosaic goes toneless to Orcus below.

|

The next passage, Das Menschen und Götter bezwinget, Nicht die eherne Brust rührt es des stygischen Zeus, is sung mostly a cappella, with occasional punctuation from the brass. It receives a contrapuntal, but not fugal treatment, with an antiphonal dialogue between the men's and women's voices. Then, with the next line, Einmal nur erweichte die Liebe den Schattenbeherrscher, the fugal approach returns, and is answered in turn by the antiphonal, nearly a cappella response of the line, Und an der Schwelle noch, streng, rief er zurück sein Geschenk.

At this point, there is a shift. The tonal center moves to F major, and the setting continues antiphonally on the line Nicht stillt Aphrodite dem schöne Knaben die Wunde, with all voices joining to sing Die in den zierlichen Leib grausam der Eber geritzt. This latter line employs a favorite device of Brahms, the grouping of accents to create a polyrhythmic effect, and on the concluding syllable of "geritzt" ("torn") the key moves dramatically to A major. It continues in the relative minor of F# for the line Nicht erretet den göttlichen Held die unsterbliche Mutter. In the following line, Wann er, am skäischen Tor fallend, sein Schicksal erfüllt, the rhythmic device is employed again in an even more jarring way, creating great tension, and the tonal center moves rapidly and ambiguously until the final word "erfüllt" ("fulfills,") where it lands emphatically on C# major, a key that is very harmonically distant from the original key of D, while at the same time being based only a semitone away from it. The irony of this is mirrored in the lyric.

The piece remains in this key, with an exultant affect, for Aber sie steigt aus dem Meer mit allen Töchtern des Nereus, Und die Klage hebt an um den verherrlichten Sohn. With the following line, Siehe, da weinen die Götter, es weinen die Göttinnin alle, there is much harmonic tension, which is resolved once more in C# with the line, Daß das Schöne vergeht, daß das Vollkommene stirbt. "Das Vollkommene stirbt" is repeated twice more, and then these two lines, beginning with "Siehe," are repeated, this time in F#. Again, "das vollkommene stirbt" is repeated three times. On the final "stirbt" (in English, "dies") there is an abrupt transition back to the original D major, and the F# tone of "stirbt" becomes the opening tone of a return to the oboe introduction, which begins on the F# of D major.

It is this moment which is the most ironic of the piece. The oboe solo, which initially sounded somewhat bland and naive, has been transformed in meaning by the process of development that has taken place in the intervening period, and has acquired a sublime quality, which is intensified by the abrupt modulation from F# major to D major. Then the fugal theme returns in a modified form for auch ein Klaglied zu sein im Mund der Geliebten, ist Herrlich, followed by the antiphonal Denn das Gemeine geht klanglos zum Orkus hinab. Not content to end on that line, however, Brahms returns to auch ein Klaglied zu sein im Mund der Geliebten, ist herrlich, and fashions a sort of coda from it to conclude the piece, which comes to rest on the word "herrlich" ("glorious.")

Homepage  Send us E-Mail Send us E-Mail

|