Heinrich Heine and the politics of RomanticismHow did the United States, the nation that once put a man on the moon, the nation that built the Hoover Dam and the Tennessee Valley Authority, become a nation that can no longer do these things? How did the world's first constitutional republic become a nation where children take weapons to school and massacre their classmates? Or to put it more generally, why do civilizations decline? How do cultures that were once cultivated, intelligent, and progressive, become barbaric? The answer, in part, is romanticism. Romanticism was a school of thought that became fashionable in politics and the arts, beginning especially in the 19th Century, and continuing up through the present day. Lyndon LaRouche has described it as “simply the idea that the acceptance of blind passion, as such, must rule.” [FN 1] Its devastating effect on human creative mentation was subjected to intense scrutiny and ridicule by the German poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), the subject of this report.

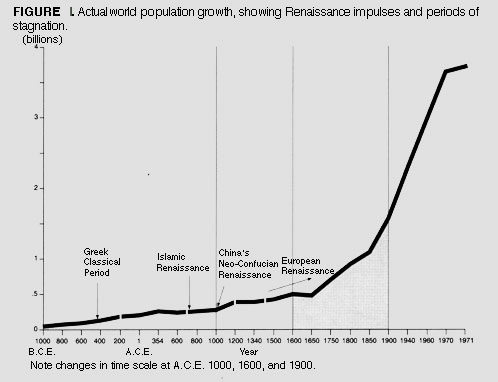

For most of human history, human societies have been oligarchical in nature, and the dominant elites have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo which keeps them in power. When a society undergoes a renaissance, the masses of people begin to gain access to education and literacy, and their sense of identity slowly changes. Instead of being simply resigned to a life of servitude, the individual member of society begins to aspire to a better life. Under these conditions, over time, social change becomes inevitable. It is for this reason that a renaissance is so bitterly opposed by an entrenched oligarchy, which prefers a fixed, static, “sustainable” social order.

It also spread to the Americas, as Europeans sought an opportunity to put renaissance ideas into practice in a location where the power of the oligarchy was not yet firmly established. The political and economic experiments in the North American colonies led to the American Declaration of Independence, the War of Independence, and the founding the U.S., which was quickly recognized as a mortal threat by the European oligarchy. The European oligarchy and its court philosophers set into motion counter-measures which assumed the form of what is called romanticism. Some major facets of this movement included:

2. The "Noble Savage". This was a concept, promoted in literature and elsewhere, which suggested that humans were better off without the corrupting influence of literacy, science, and civilization generally. In recent times this image has been embraced by the environmentalist movement, because the "noble savage" leaves a very small "environmental footprint" - the goal is have the same static relationship to nature that animals do. And of course, to further blur the distinction between humans and beasts, we have the Animal Rights movement.

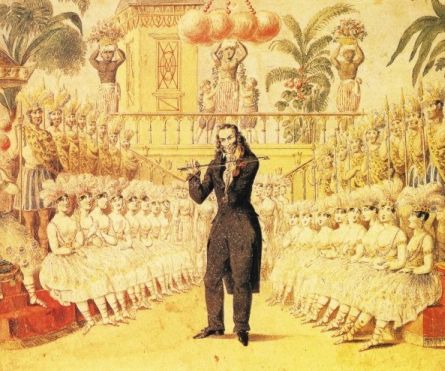

Initially influenced by romanticism, Heine was quick to see its flaws. He did not have the intellectual stamina of a Friedrich Schiller, who constructed a complete and rigorous system of aesthetics to oppose it; instead, Heine deployed his particular gift, his wickedly sardonic sense of humor. As a young man, Heine was strongly influenced by Miguel Cervantes, who wrote the definitive satire of chivalry in his Don Quixote. In 1837, at the age of 40, he wrote an introduction to the immortal satire, in which he said the following: "...What fundamental idea guided the great Cervantes, as he wrote his great book? Did he intend only the ruin of the Romance novel, the reading of which was all the rage in Spain at his time, so much so that spiritual and secular prohibitions went unheeded? Or did he want to hold up to ridicule all manifestations of Romantic enthusiasm, particularly heroism? Evidently he aimed at a satire against the aforementioned novels, which he, by illuminating their absurdities, wanted to bring to general mockery and downfall. In this he succeeded most brilliantly: for what neither the admonitions of the pulpit nor the threats of the chambers could accomplish, was effected by a poor author with his quill: he wrecked the romance novel so thoroughly, that soon after the appearance of "Don Quixote" the taste for those books died out throughout Spain, and no more were printed. But the quill of the genius is always greater than he himself, it reaches out beyond his intentions of the time, and without his being clearly conscious of it, Cervantes wrote the greatest satire of Romantic enthusiasm." Four years later, for reasons of health, Heine took a vacation in the Pyrenees mountains in the northerly Basque region of Spain, which became the setting for "Atta Troll – A Midsummer Night's Dream", Heine's own great satire. There is no facet of romanticism that escapes Heine's penetrating gaze. Heine selects as the protagonist for his mock-saga a dancing bear, an image that is thoroughly and essentially comical. In the course of the poem, his bear escapes captivity, and proclaims himself the leader of a revolution against the dominion of humans. He makes political orations laced with quasi-Marxist rhetoric, and holds forth about the profound artistry of his dancing. The bear becomes the perfect vehicle for tweaking every kind of self-important and pompous fool on Heine's long list of candidates. The poet makes analogies, comparing his bear to epic heroes such as Odysseus, of Homer's “Odyssey”, and Roland, celebrated in the “Chanson de Roland” and “Orlando Furioso” (the Pyrenees were the site of the epic battle where Roland fell, and Heine makes the same location the site of Atta Troll's demise.) He takes aim at the Gothic novel by means of his character Uraka, widely believed to be a witch, and her son Laskaro, widely believed to be a dead man, brought back to life by mother's magic potions; Uraka lives in a quaint little hut, perched on the mountainside, full of herbal remedies and stuffed vultures. Heine takes a swipe, in passing, at the musical romanticism of Giacomo Meyerbeer, and spends a chapter mocking the Swabian school of poets which produced Uhland, Mörike, and Kerner. True art does not moralize or tell the listener what to think; instead, it presents ironies that awaken in the mind a sense of its own power, the power to resolve metaphorical paradoxes that would stymy the smartest computer or dolphin. Heine understood this all too well, and his epic never becomes a soapbox. His commentary is always woven seamlessly into his narrative, and at the beginning of chapter three, he announces his disdain for didacticism: Dream of summer nights! Fantastic, Pointless is my song. Yes, pointless Just like love, or just like living, Like creator and creation! Only its own zest obeying, Whether galloping or flying, In the realm of fable bustles My belovéd Pegasus. Not a virtuous and useful Cart horse for the bourgeoisie, Nor a mount for warring parties That, pathetic, stamps and whinnies![FN 3] In Heine's foreword to the poem, he comments on the then-popular Tendenzdichter, the German poets who used poetry as a vehicle for political commentary: "The muses received strict instructions, that henceforth they should not gad about idly and frivolously, but rather they should enter into the service of the fatherland, like perhaps commissary cooks for Freedom or as washerwomen for Christian-German Nationhood." Heine says that he drew inspiration from the popular poem "Der Mohrenfürst" ("The Moorish Prince",) a prototypical depiction of the Noble Savage. In the poem, the black African warrior chieftain is defeated and captured by white Europeans, who make him an attraction in a traveling circus, breaking his noble spirit. While acknowledging the skill of the author, Ferdinand Freiligrath, Heine states that poem nonetheless had a comic effect on him, and the African prince became the model for Heine's dancing bear, who, tired of the humiliation of captivity, makes his escape and vows to lead a rebellion of the animals. Ultimately, Heine delivers a devastating blow to romanticism, not by making strident denunciations, but rather by following in the path of Cervantes, and "illuminating its absurdities." As Heine puts it in his foreword, "...I wrote it for my own joy and pleasure, in the whimsical dreaminess of that Romantic school, where I lived out the most pleasant years of my youth and finally thrashed the schoolmaster." EXAMPLESAtta Troll as the Romantic artiste: here the bear is reunited with his sons and daughters, after escaping from the humans, and describes for them his career as a dancer.Gladly then the old one tells them What he's lived through in the world, How so many men and cities He has seen, and how he's suffered, Like the son of brave Laertes,[FN 4] Only with a single diff'rence, That his wife did travel with him, Yes, his black Penelope. Also speaks then Atta Troll Of colossal acclamation That, for his display of dancing, He received from all the people. He assures them, young and old Cheered him on in admiration, When he danced at all the markets To the bagpipe's dulcet crooning. And the ladies, most especially These most tender cognoscenti, Had applauded him so madly And their eyes had paid him homage. Oh, the vanities of artists! Smiling now, the elder dance-bear Thinks upon the times his talent Was displayed before the public. Overcome by selfish rapture, He will by the deed express it, That he's not a sorry braggart, He touched greatness as a dancer - Suddenly he springs to motion, Rears aloft on his hindquarters, Like in former times he'll dance his Dance of dances, the Gavotte. Mute, with muzzles hanging open, All the youngster bears behold it, How the father leaps, prodigious, To and fro out in the moonlight. Atta Troll as the revolutionary firebrand: here the bear orates to his children. Heine, who as a Jew had experienced anti-Semitism, includes a parody of it here."Children" - rumbles Atta Troll, And he wallows to and fro On the bare and stony litter - "To our kind belongs the future! Were each bear and were each other Animal to think as I, With united forces we should Wage a fight against the tyrants. Let the boar conjoin his powers With the horse, the elephant Wind his trunk with love fraternal 'Round the doughty oxen's horn; Bear and wolf, of ev'ry color, Buck and monkey, and the rabbit, Working for a time in concert, Victory could not elude us. Unity, the first requirement Of our time. While separate, we Were their servants, in alliance We'll outwit the lords of power. Unity! and then we triumph, Down shall fall the regiment Of the snide monopoly! We'll Found a fair and beastly realm. Basic law shall be alikeness Of God's creatures, one and all, No distinction made of faith, and None of pelts, and none of odors. Strict equality! Each donkey Authorized for high state office, And the lion shall, in contrast, Trot the feed-sack to the miller. As concerns the dog, he is most Likely a submissive pooch, For throughout the centuries did Humans treat him like a dog; But in our Free State, we'll give him Back his everlasting rights, the Rights which can't be alienated, And he soon shall be ennobled. Yes, and even Jews shall have them, They'll enjoy full civil rights, And by law be viewed as equals Of the other mammal species. Only dancing at the markets Still shall be forbidden to them; I am making this amendment In the int'rests of mine art. For, the sense of style, of forming Strict development of motion, This the Jewish race is lacking, They would ruin the public taste." Heine pokes fun at the Gothic Novel: here Heine has entered the poem in the first person, hunting Atta Troll with his local guide, Laskaro.On a slope so steep and scary, Like a sentry peeps into the Vale Uraka's little dwelling; There I went behind Laskaro. With his mother he conferred, in Very secretive sign language, As to how our Atta Troll Could be lured, enticed and slain. For we'd tracked his many travels Very well. No longer could he Possibly outrun us now. Thy Days are numbered, Atta Troll! As to whether old Uraka Really was a most distinguished, Mighty witch, as many people In the Pyrenees maintained, I will not be passing judgement. This much do I know, that on the Outside she looked quite suspicious. Weeping crimson eyes, for instance. Mean and squinting is her gaze; And 'tis said, that when she casts her Eyes upon a cow, its udder Suddenly goes dry for milking. Everyone assures me, that by stroking with her scrawny hands, she Killed fat swine in goodly number, And as well the strongest oxen. Now and then she was accused of Misdemeanors of this nature, To the magistrate. But this one, He was a Voltairean, Yes, a modern, vapid worldling, With no faith and with no substance, And the plaintiffs were dismissed with Skepticism, almost mocking. For the record, this Uraka Had an honorable business; For she dealt in mountain herbs, and Also various stuffed birds. Full of such organic products Was the hut. It smelled so frightful, Reeked of henbane, cuckoo flowers, Mandrake roots, and dead-man's-lilacs. Prominently on display was Her collection of stuffed vultures, With their wings outstretched for flying, And their beaks, so large and monstrous. Was the smell of crazy plant life What I found so stupifying? I began to feel so wondrous At the sight of all these vultures. Maybe they're accurséd people, Who, through means of magic potions, Find themselves unfortunately In this sad stuffed bird-condition. Gazing at me, pained and rigid, At the same time so impatient; Often they did seem to shyly Squint back at the witch behind them. She, however, this Uraka, Crouches down next to her offspring, Son Laskaro, at the chimney, Heating lead and pouring bullets. So they cast that fateful bullet, By which Atta Troll did perish. How the flames flared up abruptly Over that old witch's visage! She doth keep her thin lips moving Constantly, but also soundless. Murmurs she the druids' blessing, For the bullet-mold to prosper? Now and then she snickers, nodding To her son. But he goes on to Expedite his business, ever Grave and silent, just like death. - Posted by permission of the translator ~ © 2005. For the full translation of Atta Troll, click here. ______________________________________________________________ Footnotes: 1. “Dialogue with LaRouche”, EIR, November 14, 2003, p. 42 2. This practice was made the butt of many jokes in Mozart's "Marriage of Figaro." 3. This passage may be usefully compared to Schiller's "Pegasus in Harness." 4. Odysseus.

|